Give it up for the Hippocampus

How do we know things? How do we know each other, ourselves, names of objects and historical events? How do we know where we left our keys or why we came into a room? We know these things because we have a memory of them, of course.

It’s not unreasonable to assume that most, if not all, seniors are concerned about their memory and their general cognitive function as well. Fortunately, we need not be greatly concerned if we can’t remember why we are standing in the middle of the kitchen or where we put our cell phone. This happens to everyone, not just seniors.

It does happen more frequently with seniors than with younger people though. This age-related increase in mild memory impairment is normal. I sometimes laugh at myself when I’m standing in front of an open refrigerator wondering what it was I needed.

In his book Successful Aging, Daniel Levitin shared a joke that is apparently popular with memory researchers:

Two elderly gentlemen are sitting next to each other at a dinner party.

“My wife and I had dinner at a new restaurant last week,” one of the men says.

“Oh, what’s it called?” the other man says.

“Um…I…I can’t remember.” (Thinks. Rubs chin.)

“Hmm…What is the name of that of that flower that you buy on romantic occasions? You know, it usually comes by the dozen, you can get it in different colors, there are thorns on the stem…?”

“Do you mean a rose?”

“Yes, that’s it!” (Leans across the table to where his wife is sitting.)

“Rose, what was the name of that restaurant we went to last week?”

As is true of other parts of our neurological systems, memory has evolved to help us adapt to the demands of the environment. There are several systems accountable for memory, and each is associated with specific anatomical area(s) of the brain. But before we start drilling down into brain parts, let’s look at how memory works and the types of memories we have.

Types of Memory

We have several different memory systems. Spatial memory allows us to know where we are. Procedural memory helps us remember how to perform simple tasks like using a faucet or activating the turn signal on our car. Short-term memory allows us to remember information we learned just a few minutes ago.

According to Levitin our memory systems form a hierarchy. Spatial, procedural, and short-term memory each use different neural circuits in the brain, and each is vital for daily functioning. But above them, at the top of the hierarchy, are implicit memory and explicit memory.

Implicit memory is the type of memory that we use to perform complex behaviors like playing the piano or tennis. Once these behaviors are learned, we do them automatically without having to think about them or consciously reconstruct them.

Explicit memory, on the other hand, includes two types of memory: semantic memory and episodic memory.

Sematic memory is the memory of general knowledge. This memory includes all the things and information we know but don’t remember learning. It’s knowledge we know so well that we take it for granted. For example, what is the capitol of Russia? Moscow, of course. But when did you learn that?

After so many decades spent acquiring knowledge, we older adults have a lot of information stored in sematic memory. According to professor Alan Castel in his book Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging we sometimes have trouble retrieving general knowledge because we have so many semantic memories in our brains that they become cluttered. The sheer volume makes semantic memories harder to find and affects our recall.

Episodic memory, on the other hand, is the memory of all those things we know from particular events or episodes in our lives. Your wedding, the birth of a child, the funeral of a loved one. We remember these events because we were in them. We were there. What differentiates episodic memories from semantic memories is they have autobiographical components to them.

I recall that in 2007 I was a graduate student sitting in a conference room with three professors giving an oral defense of my dissertation. My committee members asked me a series of questions and asked for explanations of various points I made in my research. When they were done, they asked me to leave the room so they could discuss my work. In about 20 minutes they called me back into the room. I sat down at the table. My Chair stood up and extended her had. I took it and she said, “Congratulations, Dr. Lopez.”

I was so happy I almost started crying. Earning my doctorate at 59 years old was one of the seminal moments of my life. I remember every detail about that room and the members – their names, where they were sitting, even the items on the table in front of them. Heck, I even remember what color blouse my Chair wore that day. That is an episodic memory!

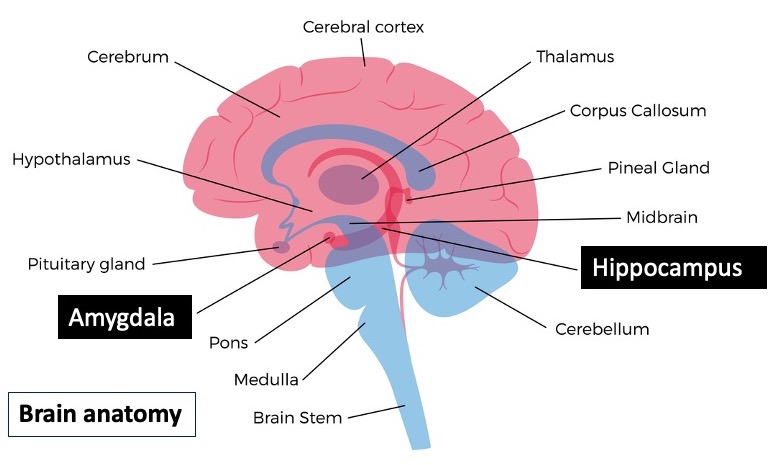

One thing we can glean from the example above is that emotion is a key factor in remembering. Even if the emotion is negative. This is true because the area of the brain that facilitates the storage of emotional memories–the amygdala–is active when we store emotional memories and less so when we store semantic memories. Semantic memory events rely more heavily on another area of the brain–the hippocampus.

The Aging Brain

One of the things we do well at when it comes to memory is recalling emotional information. This is probably because these memories carry greater importance for us and because emotions activate the amygdala. And the amygdala tends to continue to perform well even as we age.

On the other hand, the hippocampus, which is the area of the brain responsible for storing all memories, and general memories in particular, declines in volume by about 1% a year after the age of 50.

The hippocampus is a sort of gate keeper for all memories. Even though our memories are not actually stored there, the hippocampus is responsible for the dissemination of information to various areas of the brain where information is turned into memory.

HM: A Case Study

While researching this article, I dug out an old textbook I used when I taught undergraduate psychology–Foundations of Biopsychology by Andrew Wickens–and read the chapter on memory. In his book, Wickens describes a classic case study of a person known only as HM, a study from which we learned a great deal about the role of the hippocampus.

HM was born in 1926. At the age of 9 he had a bicycle accident and injured his head. He began having seizures, which increased in severity over time. By his late twenties, HM had such severe seizures that he could no longer work. After several attempts to correct the problem with toxic levels of medication, his doctor decided it would be helpful to remove his hippocampus. (What were they thinking?)

The operation was a success in that it stopped the seizures, but the side effects were disastrous. HM was no longer able to store information into long-term memory. HM suffered a profound case of anterograde amnesia. (Antero means “in front”.) He had good language skills, a good vocabulary, and above-average IQ. He could remember things from his past, but after the surgery he had only short-term memory. He could not consolidate any new long-term memories. A researcher who worked with HM for 40 years had to reintroduce herself to him every time she came to work with him.

What can we learn from this case? Maintaining the health of the hippocampus, is essential if we are to continue acquiring new long-term memories.

What Can We Do?

Fortunately, there are things we can do to support good brain health and even increase the volume of the hippocampus.

In Successful Aging1, Levitin references a book written by a neurologist Scott Grafton, Physical Intelligence: The Science of How the Body and the Mind Guide Each Other Through Life. Grafton points out that when thinking about brain health, the idea of a brain/body dualism is unproductive. The focus should be on the health of the whole organism not just the brain. You can’t separate the two.

Grafton argues that the single factor with the largest effect on mental health is exercise and physical activity in general. “We now have hundreds of trials with thousands of subjects” that show the benefit of physical activity.

In addition to exercise, Grafton also believes we benefit from “…problem solving, social enrichment, mind body coordination, and fresh air.”

So, should we all run out and buy a treadmill? Well, a treadmill may get oxygenated blood to your brain, but that’s not the whole picture. Yes, Levitin points out, “A systematic meta-analysis showed that for adults with mild cognitive impairment, exercise had a significant beneficial effect on memory.” But what about problem solving, social enrichment, and fresh air?

Okay, how about tennis? I don’t know how to play tennis. So, if I took it up, I would have to learn how to play. That would certainly involve mind-body coordination and problem solving as I dash around the court trying to figure out where the ball is going and how I need to swing the racket to be effective. Since, unlike a treadmill, I would need to find people to play with, I would probably make new friends. I think that would constitute social enrichment. And, unlike a treadmill, I would be outside in the fresh air.

Of course, few of us are likely to take up tennis as we age. So is there a happy medium?

The truth is, you don’t have to buy a treadmill or take up tennis to engage in healthful physical activity. Walking works. Just walk at a pace that moves you out of your comfort range to get your blood flowing.

Ideally, walk on a path in a park or in the wilderness. The constant need to make physical and spatial adjustments while walking on an unpaved surface stimulates the neural circuits in the brain and helps keep your navigational skills and memory systems in shape. The area most stimulated by those adjustments is the all-important hippocampus.

Need evidence? A study was done using a group of seniors that walked for 40 minutes three times a week and comparing them to a group of seniors that did stretching exercises three times a week. The study concluded that the average walking group member’s hippocampus increased in size by about 2% after one year.

So, if you want to stay sharp and slow the inevitable decline of your brain, and hence your memory, the best thing you can do is stay active. Do something that will get oxygen to your brain and require you to keep your brain focused on what you’re doing. And try to do it with other people.

Oh, and just for fun, see how a “memory athlete” can remember the first 10,000 digits of Pi.

Ed Lopez, PhD, Love of Aging’s Science Editor is a retired organizational psychologist, university instructor and researcher. His research has been presented at international conferences and published in a peer reviewed journal. Ed is also a decorated Army veteran who served in Vietnam.

Ed Lopez, PhD, Love of Aging’s Science Editor is a retired organizational psychologist, university instructor and researcher. His research has been presented at international conferences and published in a peer reviewed journal. Ed is also a decorated Army veteran who served in Vietnam.

hown that active and productive engagement in society is a key element in successful aging. When seniors increase their levels of social participation, we have a reduced rate of suicide, better physical health, reduced mortality in general, and higher levels of psychological well-being.

hown that active and productive engagement in society is a key element in successful aging. When seniors increase their levels of social participation, we have a reduced rate of suicide, better physical health, reduced mortality in general, and higher levels of psychological well-being.  Formal. These types of opportunities tend to be more formally organized and involve the delivery of services. These roles tend to be more strictly supervised and more highly structured.

Formal. These types of opportunities tend to be more formally organized and involve the delivery of services. These roles tend to be more strictly supervised and more highly structured. oaching a sports team, or pick up some valuable teaching experience by tutoring literacy courses.

oaching a sports team, or pick up some valuable teaching experience by tutoring literacy courses.

Research has also

Research has also